To paraphrase M. Scott Peck, life is difficult, and once we accept that, we can transcend it. Much of this difficulty stems from the dysfunction we all have in our family of origin. There are generational messages transmitted, both purposefully and otherwise, that impact our lives.

So no family is perfect – and when we look to scripture we see this emphasized. The families in Genesis paint a clear picture of dysfunction and generational trauma. From Cain & Abel to the Jacob/Rachel/Leah love triangle, we get many, many stories of people chosen by God but still hurting within themselves and hurting others. But out of that chaos comes the legendary 12 Tribes of Israel, the People of the Covenant the line of Christ and the mechanism by which God saved the world.

We can take some comfort in this, that we are not alone – there is nothing we have ensured or are enduring that God has not seen before, that God has not used for the good of His people and the glory of His name.

The dynamics in our families of origin still impact us. They help determine how we interact with people we love, what we value, and how we respond to both hurt and success.

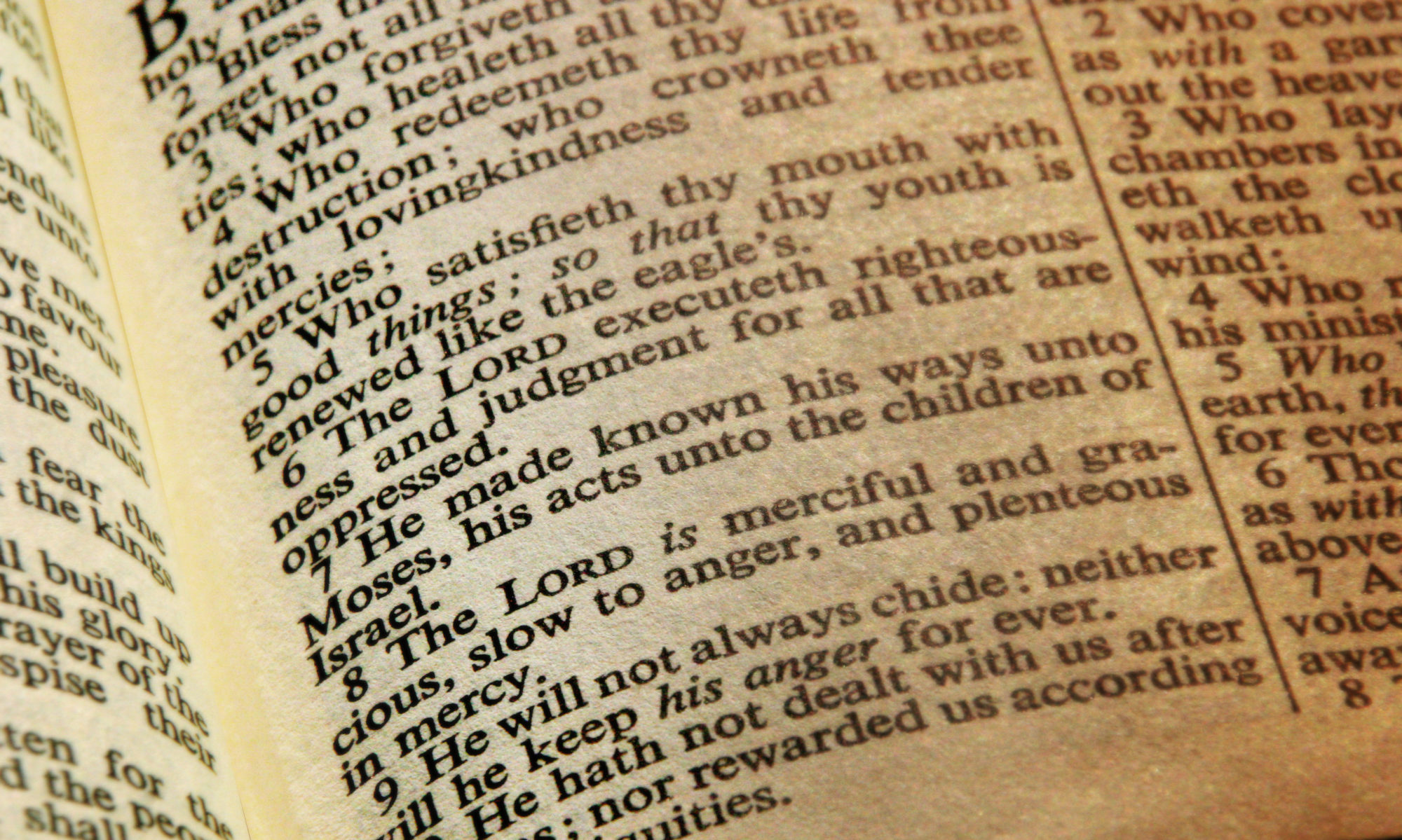

Scripture tells us that the sin of parents impact their children and their children’s children (Exodus 34:7). But it also tells us that His grace is even more pervasive.

We get a picture of this grace and healing in a family, also in Genesis. Joseph came out of this same dysfunctional brood, with favoritism, pride and jealousy all coming together to leave him considered dead by his family and enslaved in a foreign land. But Joseph turns his focus to following God even in his circumstance, so that when he is brought face to face with the brothers who wronged him, he (eventually) finds a way to forgive and find healing. First, though, he is overcome and finds a private room in which to weep. What are your private rooms, where you go to when triggered by a reminder of past hurt?

When Joseph finally confronts his brothers, he does so with mercy and forgiveness that is nearly unfathomable. The story of Joseph is the story of the Gospel, turning trauma and tragedy into salvation.

In the same way, our misery becomes our ministry. When God takes us through healing, He gives us the words and the ability to reach others with that same message of healing. Sometimes that trauma itself will even push us to God and to that healing.

Joseph’s brothers deserved to be cursed and to have revenge taken on them. Instead, God made their sin the mechanism of material salvation for their family, and even of healing for the relational trauma of the family.

What are the traumatic events of your past that have wounded you? God is big enough. There is nothing too bad or too overwhelming such that He cannot bring healing and redemption.

— Sermon Notes, Dave Sim, Renew Church, Lynnwood WA, June 2, 2024