Advent is a time of anticipation of the coming of Christ, both as a memory of what happened historically, and as a coming into our lives to transform us. It’s a time of joy, also, joy in gifts and presents and songs – but as we grow in maturity, the more we see that patience and anticipation as a core part of the joy. To persevere for a good thing and finally grasp it, that is true joy. This us something we learn better as we age, though aging also comes with disappointments. Financial, relational, emotional, even faith related.

The time of Advent also comes when the world is drenched in consumerism and business. What had been a time of waiting leading up to the feast commemorating Christ’s birth has become a secular frenzy of spending and accumulating.

What we are called to do in Advent, though, is to wait in hope. Those are not exactly the same thing. One can wait without hope, but hope is a leaning into a future that is greater than what we have today.

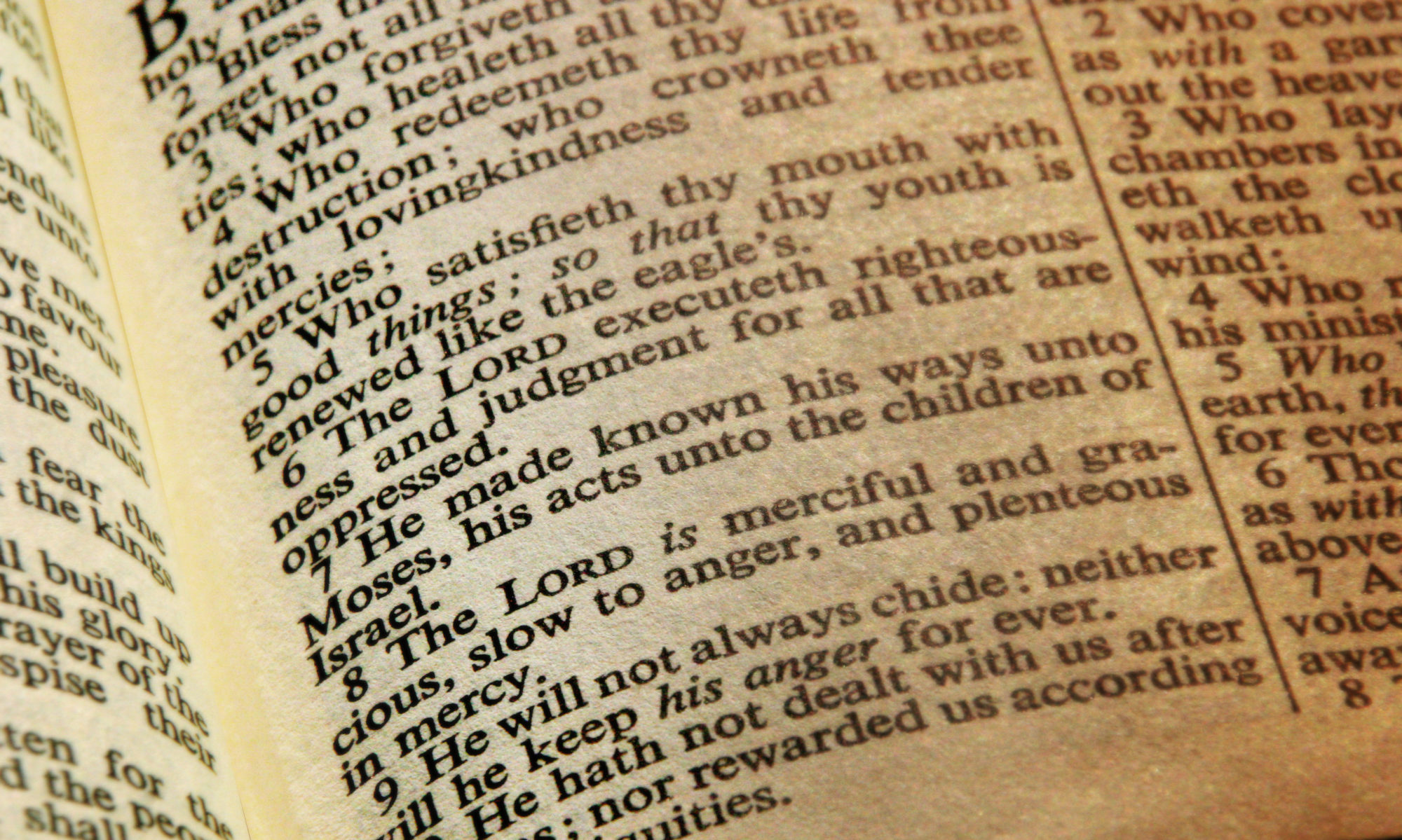

We see that in today’s passage, written by the prophet Jeremiah in a time of upheaval and turbulence. This promise comes in the midst of condemnation of the nation of Judah. The people are breaking the Covenant of God both with idol worship and social injustices. Jeremiah warns the king of Judah, Zedekiah, not to be making alliances that will bring Babylon down on them.

In the midst of that, Jeremiah gives a promise from God – that He will raise up a “righteous branch” who will do both what is right and just, addressing both the idolatry and injustice of the present time. A leader will come who will embody all the goodness of God, who will make His people both saved and safe. Verse 16 promises both of these, again addressing both the material and the spiritual.

His name will be “The Lord is Our Righteousness.” We can look back and see this as a promise of Jesus who, through His life, death and resurrection, becomes our righteousness.

What are the promises of God? Love and Faithfulness; Strength and Help; Presence and Guidance; Provision; Peace; Forgiveness; Eternal Life and Salvation; Rest.

And that rest is a deeper and truer rest than laying around on the couch, but rather a total fulfillment of our anxieties and desires.

That promise is coming – let us seek to imitate it and live into it as best we can, especially in this season of waiting and anticipation.

— Sermon Notes, Dave Sim, Renew Church, Lynnwood WA, December 1, 2024